“We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us,” is a popular adage among architects which was first coined by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Its sentiment could also be applied more widely: We shape our cities and afterwards they shape us. After all, it has become clear that how cities evolve has an impact on each and every one of us.

Around the 1960s, the idea took hold in numerous industrialized countries that residential and industrial areas should be separated and, initially, that had many benefits. Both industry and delivery traffic for retailers create noise and air pollution and generally lead to a lower quality of life than in a purely residential area. But this separation also has its drawbacks, such as increasing the number of individuals commuting each day. A phenomenon such as rush hour only exists because so many people are criss-crossing the city at the same time.

Stuck in traffic for 272 hours every year

The latest edition of the annual INRIX Global Traffic Scorecard Report lists record figures for traffic jams in cities around the world. In Colombia, every Bogotá resident spends an average of 272 hours stuck in traffic; in Rome it is 254 hours, in Paris 237 and in Berlin and Boston more than 150 hours. People are spending hours of their lives waiting bumper to bumper.

An increasing number of factors contribute to these jams: In addition to commuters on their way to work, the list now also includes a number of delivery services. In Germany, the revenues from courier, express and parcel services has roughly doubled in just 15 years. Individuals who live in Germany, the UK and the US receive around 20 packages annually, while in China, the figure is an astounding 70 per person. One of the reasons is the acceleration of e-commerce. It is a megatrend which sees KION Group also benefiting from it since warehousing and supply chains have become increasingly important.

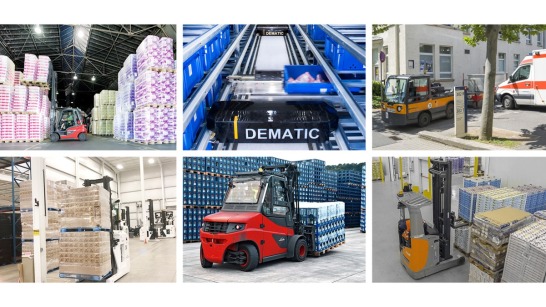

Though e-commerce grew by a remarkable 8 percent worldwide in 2015, it is closer to 20 percent today, with a forecast of even faster growth. And online retailers will be expanding their product ranges even further in the future, including developing their food offerings. What is often forgotten in all this is that package companies account for just a portion of all delivery traffic. “They get by far the most media attention, but the package delivery companies actually only represent about 20 percent of delivery traffic,” says Markus Schmermund, a vice president of Automation & Intralogistics Solutions at Linde Material Handling.